Happy Mother’s Day to All Our DuMA Moms!

“To describe my mother would be to write about a hurricane in its perfect power. Or the climbing, falling colors of a rainbow.”

-Maya Angelou

DuMA Holiday 2024 Hours: Closed December 25th and January 1st.

Happy Mother’s Day to All Our DuMA Moms!

“To describe my mother would be to write about a hurricane in its perfect power. Or the climbing, falling colors of a rainbow.”

-Maya Angelou

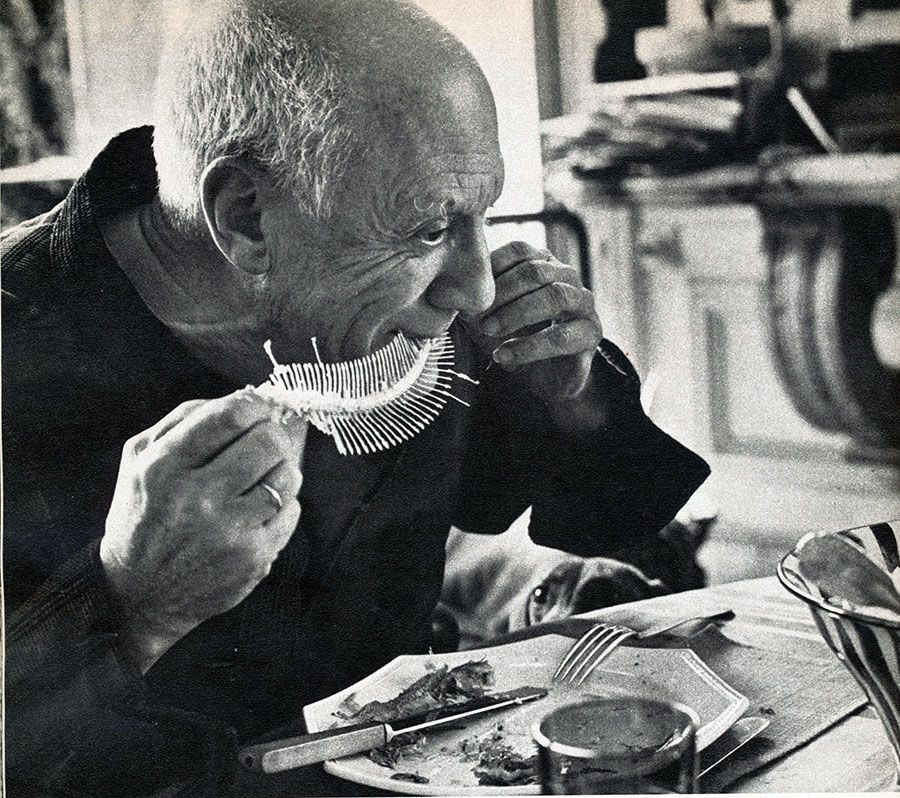

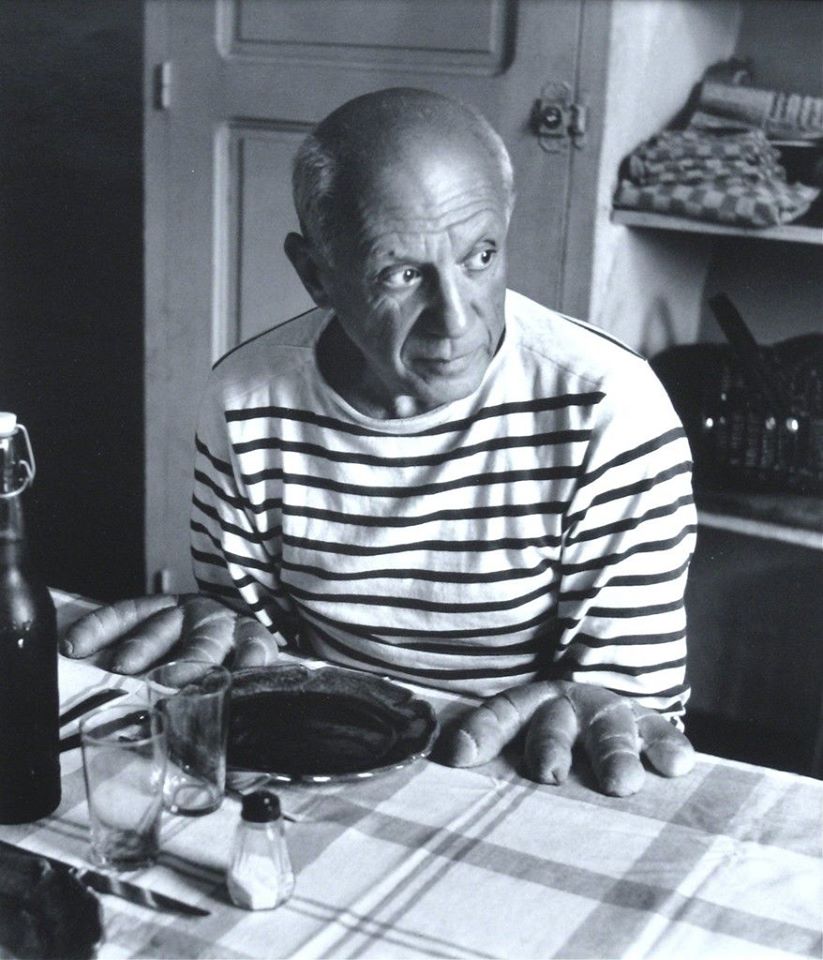

What’s Cooking? – Pablo Picasso

Spanish artist Pablo Picasso, is one of the most iconic artists of all times. Picasso was best known for his unbridled appetite for women. His diet, however, was surprisingly restricted. When he was in his fifties and plagued by worries of ill health and decreased productivity, he adopted what today would be termed the Mediterranean diet, consisting of fish, vegetables, grapes, and rice pudding washed down with mineral water or milk. He ate in silence, uttering not a word from beginning to end.

Picasso’s doctor advised him to eat spinach. One of Picasso’s least objectionable ways to consume this leafy green vegetable was in a souffle.

Spinach Souffle (vintage recipe)

(4 servings)

1 package chopped frozen spinach (1 cup)

1 Tablespoon grated Parmesan cheese

1 Tablespoon butter

2 or 3 shallots – minced

2 Tablespoons lemon juice

6 Tablespoons butter

5 Tablespoons flour

1 and 1/2 cups milk

1 teaspoon salt

freshly ground back pepper – to taste

6 large eggs

1 egg white

Preheat oven to 400 degrees.

Butter a two-quart souffle dish and sprinkle the sides and bottom lightly with Parmesan cheese.

Melt one Tablespoon of butter in a heavy saucepan and add the shallots. Cook for about three minutes, stirring once or twice. Add the thoroughly drained spinach and lemon juice and cook over very low heat, stirring frequently, until all the liquid has evaporated, which will take about 10 minutes. Set aside.

Melt the 6 Tablespoons of butter in a heavy sauce pan and, over low heat, stir in the flour with a wire whisk; remove from heat.

Meanwhile, bring the milk to the boiling point and add it to the butter-flour mixture, beating vigorously with a wire whisk until smooth. Add the salt and pepper and continue whisking until blended. Let this white sauce cool a little.

Meanwhile, separate the eggs. Beat the yolks into the sauce one at a time. Stir in the spinach and set the mixture aside.

Beat the egg whites, including the extra white, in a large bowl until they hold soft peaks.

Stir a little of the whites into the sauce to make it easier to manage, then gently fold in the remainder.

Pour this mixture into the prepared souffle dish. Place in oven, turn heat down to 375 degrees immediately and bake for 30 to 40 minutes until the top is well puffed up ad lightly browned.

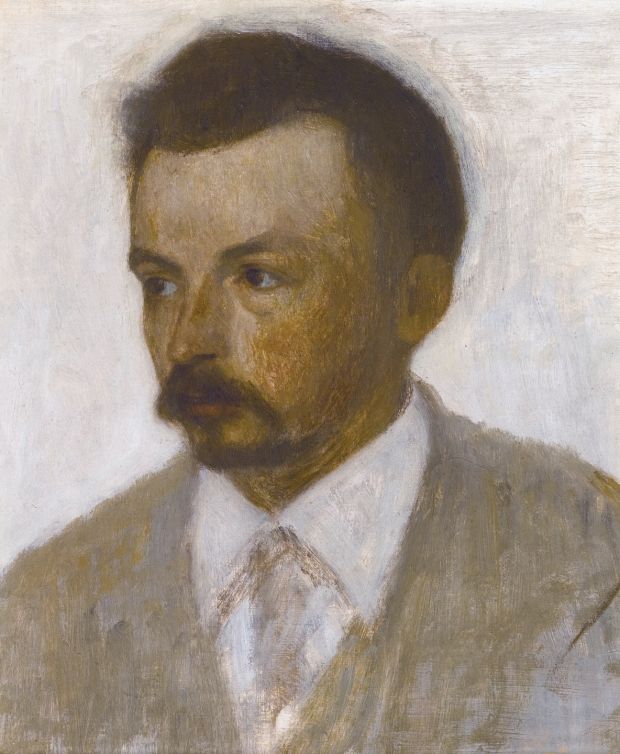

Misplaced by History-Artists Worth Knowing:

Vilhelm Hammershøi

Vilhelm Hammershøi (1864-1916) was a Danish painter known for his meditative interiors and landscapes. Created with a sensitivity to both light and spatial construction, his muted paintings use a limited palette to great effect. His figures are often positioned away from the viewer and project an air of mystery.

Hammershøi was born in 1864 in Copenhagen, Denmark. The son of a well-to-do merchant, he studied drawing from the age of eight before embarking on studies at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts.

By the age of 17, Hammershøi had chosen his themes: portraits of family and close friends, spare interiors and a few landscapes. He shunned the lively subjects and colors favored by his contemporaries, limiting his palette to subdued grey, blue, black, white and ochre.

Hammershøi worked mainly in his native city, painting portraits, architecture, and interiors. He is most celebrated for his interiors, many of which he painted in Copenhagen. By 1885, his work had taken on the formal and emotional characteristics of Dutch artist Johannes Vermeer. His early works, with their simplicity and recording of the “banality of everyday life”, enjoyed critical acclaim. Artists and literary figures of the time, among them Emil Nolde and Rainer Maria Rilke, admired his work and sought out his company. They remarked on Hammershoi’s retiring manner and reluctance to talk.

Hammershøi took few risks and never explained his art. As his library of art journals testifies, Hammershøi was exposed to contemporary art movements but consciously chose to ignore their “contaminating” effects.

Painting slowly, Hammershøi completed only 400 canvases. He expressed admiration for only one other painter, the American James McNeill Whistler. As an homage to Whistler’s iconic portrait of his mother, Hammershøi painted his mother Frederikke seated in profile.

Hammershøi’s also contributed to a new model in Scandinavian interior design, with his rejection of the cluttered nineteenth-century aesthetic in favor of a simplicity that bordered on the ascetic.

Successful during his own lifetime, Hammershøi died in 1916 in Copenhagen. In 2008, the Royal Academy of London put on the first major exhibition of his work in Britain, “Vilhelm Hammershøi: The Poetry of Silence.” Today, the artist’s works are held in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, the National Gallery in London, and the Ordrupgaard Collection in Charlottenlund, Denmark, among others.

From The Collection: Outdoor Edition

We invite you to hop in the car and go for a drive by DuMA. When you get here, pull over and check out our two outdoor sculptures located off 7th Street.

(Left) Dubuque artist John Anderson-Bricker’s sculpture, Hairball, takes inspiration from the distinctive regurgitations of a beloved family cat. Created from heavy industrial materials and covered in a delicate mosaic, Anderson-Bricker’s oversized “hairballs” are suspended in an articulated steel frame. Using scale to great effect, he playfully transforms them into a monument akin to a towering cat toy only the most fearless feline would take on. Artists often turn to industrial materials to convey their understanding of the natural world. Conversely, natural imagery can be used by artists to understand the industrial and technological elements of our culture. In Hairball, Anderson-Bricker’s ruminations take a lighthearted approach as he explores the artistic connections between the natural and the industrial world.

(Right) Tom Gibbs, Obelisk Number 3. The shape of the obelisk has a long history originating in Ancient Egypt where it was used in funerary and religious ceremonies. This stately form has been widely adopted, from the Washington Monument to countless cemetery headstones, for the gravitas it imparts. In this work, Dubuque native, artist Tom Gibbs uses the obelisk to represent the erosion of time and the imprint of history – a vanitas painting in steel. Obelisk #3’s exposed midsection, heavy gashes, and distressed surface reveal the deterioration process. The industrial steel that it is made from and the machine-made patterns in the exposed areas connect this ancient monument to the modern day. This work also connects the museum to its history. From the 1970s to 1999 the museum was housed in Dubuque’s Old Jail, one of the few Egyptian Revival style buildings in existence.

Emily Carr was a Canadian artist and writer credited as one of the first painters in Canada to adopt a modernist and Post-Impressionist style. Her paintings were inspired by the Indigenous cultures of the Pacific Northwest Coast.

Carr ventured into the wilds of British Columbia, roamed its forests and hills. There, she met the province’s indigenous people. They became her friends, and even gave her the nickname of the Laughing One. Carr sought to capture the vanishing arts and customs of Canada’s native people as well as the vast landscape she loved so profoundly.

Carr was fascinated by animals. She had parrots, chipmunks, a raccoon, white rats, cats, dogs, and a Javanese macaque monkey named Woo. Carr lived and painted them. She took them camping and even pushed some of them in a baby buggy around the town of Victoria where she lived.

“Joy blooms where minds and hearts are open.”

-Jonathan Lockwood Huie

Pairing artwork by iconic artists with music to provide you with a moment of respite and distraction.

What ‘s Cooking? The Futurist’s Cookbook

Futurism was an Italian art movement of the early twentieth century that aimed to capture in art the dynamism, speed, energy and power of the machine and the vitality, change, and restlessness of modern life.

Futurism was launched by the Italian poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti in 1909, when he published his Manifesto of Futurism on the front page of the Paris newspaper Le Figaro.

Futurism denounced the past and the oppressive weight of cultural history. The Futurist’s proposed an art that celebrated the modern world of industry and technology:

“We declare…a new beauty, the beauty of speed. A racing motor car…is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.”

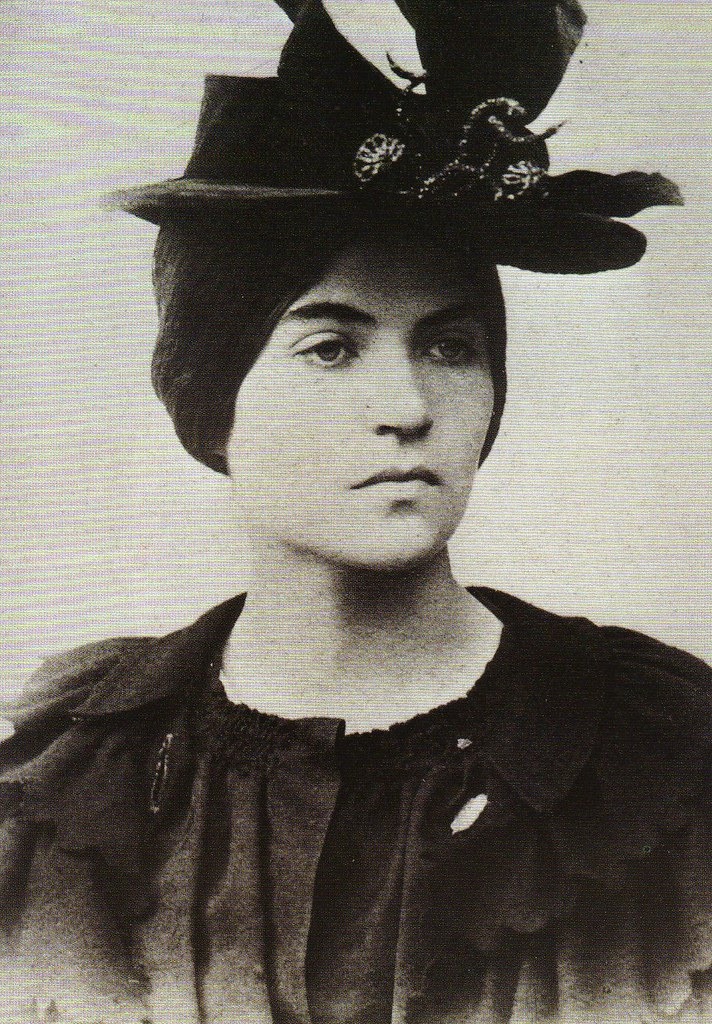

Misplaced by History–Artists Worth Knowing:

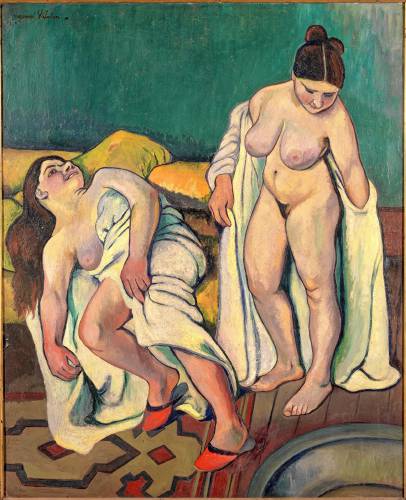

Suzanne Valadon

Suzanne Valadon (1865-1938) was groundbreaking French painter who lived and worked according to her own rules. Living at the epicenter of artistic Paris, she was a model and friend to some of the most famous artists of her generation. Her paintings of women were based on real emotions and actual physical experience, and she inspired women to look and think for themselves when such behavior was not supported.

Valadon was born near Limoges in 1865, her mother a laundress and her father unknown. As a teenager she worked as an acrobat in a circus, but when she was 16 years old, she suffered a fall. She left the circus and worked as a model for some of the most prominent artists of the time, including Toulouse-Lautrec and Auguste Renoir.

As an artists’ model, Valadon became an active member of the artistic community of Montmartre. Her personal life was colorful: Renoir was only one among a number of painters with whom she had affairs. In 1883, at age 18, Valadon gave birth on to an illegitimate son, Maurice Utrillo, who later became a renowned painter. Valadon herself seemed uncertain as to who the father of her child was.

Valadon’s first known work, a pastel Self-Portrait, dates from 1883. During the mid-to late-1880s, Valadon produced many drawings and pastels of people and of street scenes. Her artistic endeavors were assisted by Toulouse-Lautrec, for whom she often modeled and had a lengthy affair. Valadon worked to hone her skills by observing the techniques of the artists who painted her, becoming a fully self-taught artist over the years.

In 1890 she became friends with painter Edgar Degas who admired and purchased her work. Degas encouraged her efforts to become an artist and helped get her career started. In 1894 Valadon became the first woman to show at the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, a major artistic achievement.

After a turbulent romantic life, Valadon married a stockbroker who provided financial stability and allowed her to dedicate herself to drawing and painting full time.

Valadon is particularly known for her female nudes. She was among the first women to build an extensive body of work in this field, challenging the conventional portrayal of women by contemporary male artists. She placed her subjects in a living, crowded world, rather than painting them statue-like and isolated. Valadon’s unsentimental, at times edgy approach, combined with a fascination with sex and aging, allied her with Northern European Expressionists. Her unapologetic art is regarded as an art historical lynch-pin for Feminist Art.

Valadon’s home life was tumultuous. Her son Maurice began exhibiting signs of mental problems and alcoholism as a teenager, so she devoted much of her time caring for him. She encouraged him to try painting, and he soon became a successful artist in his own right. Valadon’s marriage ended in 1909 and she began a relationship with Andre Utter, an artist 20 years her junior. Valadon continued to paint and in 1911 held her first solo exhibition. Her work was acclaimed for its sensitive observation combined with bold linework and patterns. Valadon exhibited frequently in the 1920s and by the 1930’s became internationally known.

On April 7, 1938, Valadon suffered a stroke while painting at her easel. She died hours later, at the age of 72. She left over 475 paintings, nearly 275 drawings, and 31 etchings. Valadon had forged a career in a man’s world on her own terms. She had challenged the conventions of the female nude and carved a new critical space for artists to consider that genre.

Let’s Talk About Art – Salvador Dali’s The Twelve Signs of the Zodiac -Aquarius

Please Note: Let’s Talk About Art videos will now be be posted every other week on Wednesdays

Impressionist painter Claude Monet’s garden at Giverny is probably the most famous garden in France. Monet painted some of his most famous paintings while living at Giverny, most notably his water lily and Japanese bridge paintings. Monet lived in Giverny from 1883 until his death in 1926.

“My garden is my most beautiful work of art”

-Claude Monet