Misplaced by History: Artists Worth Knowing

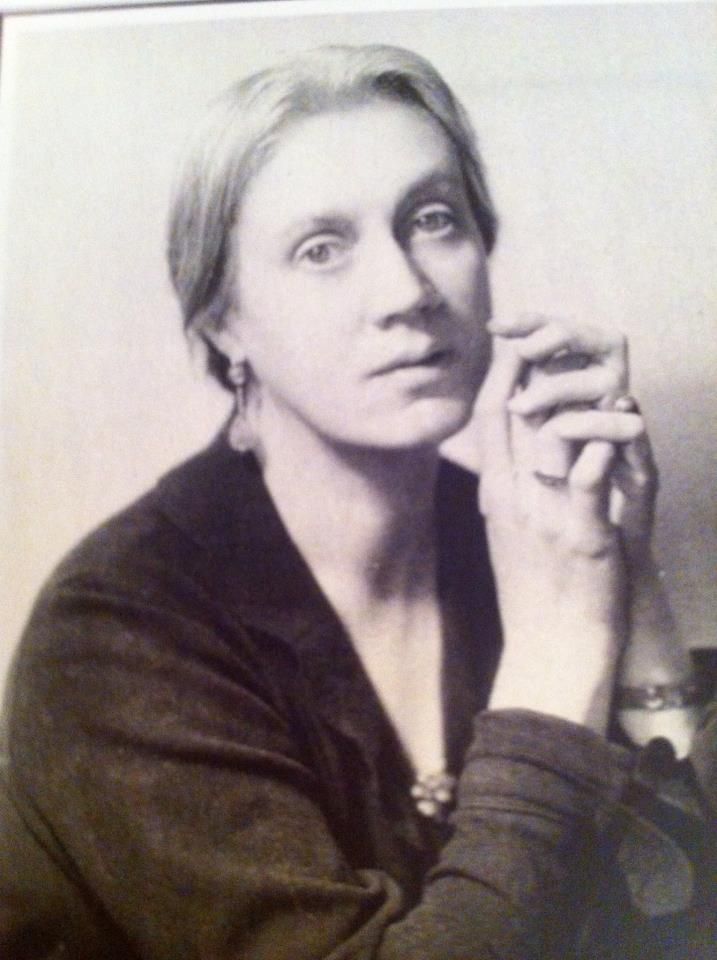

Vanessa Bell

British artist Vanessa Bell was known for her Post-Impressionist paintings which emphasized bold forms with pronounced brushstrokes and rich colors. She was also an innovator in the design world, blurring the distinction between fine and applied art. The artist’s sister, the writer Virginia Woolf, remarked that Bell’s work was as “firm as marble, ravishing as a rainbow, and like sunlight crystallized.”

Born Vanessa Stephen in 1879 in London, England, Bell was raised in an literary household where leading thinkers and artists of the time were family friends. Her father, Leslie, was an accomplished writer and editor and her mother, Julia, a great beauty immortalized by the Pre-Raphaelite painter Edward Burne-Jones and the photographer Julia Margaret Cameron.

Bell’s father encouraged her artistic talents, and in 1899 she enrolled in the Royal Academy of Arts. There, she was taught by John Singer Sargent, whose influence can be seen in the sumptuous tactile qualities and muted colors of her early work.

After the death of her parents, Bell and her siblings settled in the Bloomsbury area of London. There she met writer Clive Bell and artist Duncan Grant, founding members of what came to be known as the Bloomsbury Group. The “Bloomsberries” as they were called, were influential English writers, intellectuals, and artists who rejected oppressive Victorian institutions and embraced creative and sexual freedom. They were known for their bohemian lifestyles and complicated love affairs: the American writer and wit Dorothy Parker famously remarked that the group “lived in squares, painted in circles, and loved in triangles.”

In 1907, Vanessa married Clive Bell. They both had romantic relationships outside the marriage but remained devoted to each other.

Bell’s artistic epiphany occurred in 1910 when she attended England’s first Post-Impressionist exhibition, organized by the artist and curator, and her eventual lover, Roger Fry. There she saw the works of Cezanne, Matisse and Picasso for the first time and felt liberated by the bold, unrefined and expressive quality of their work. Said Bell, “It was as if one might say things one had always felt instead of trying to say things that other people told one to feel”

Bell embarked upon an intense period of experimentation, utilizing the vocabulary of Fauvism and Cubism in her still lifes and landscapes, as well as abstract compositions. She invented a new language of visual expression, just as her sister Virginia invented a revolutionary way of writing.

Months prior to the outbreak of World War I, Bell, her husband, and their friends, moved from the city to a country home in East Sussex. Charleston became an ever-changing work of art. Bell and her artist friends, among them Roger Fry and Duncan Grant, decorated furniture, curtains and embroideries, painted doors and walls, with their spots, swirls, arabesques, acrobats and mythic figures.

With Fry and Grant (who eventually became her longtime partner and the father of her daughter, Angelica), Bell founded the Omega Workshops, a lab to experiment with abstraction while creating beautiful and useful things for the home. Their modernist products ranged from furniture to stained glass and mosaics, as well as textiles. In 1915, Bell began to incorporate handprinted fabrics into popular dress designs. She also created the original book jacket designs for the majority of her sister novels and essays.

To Bell, art and life were intertwined and intensely personal. She died in 1961 at her beloved Charleston. Her works can be found in the collections of the Art Institute of Chicago, the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra, the Courtauld Institute of Art in London, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, among others.