In conjunction with the Craft Invitational exhibition, we invite you to explore some of the Craft movement’s leading figures and schools.

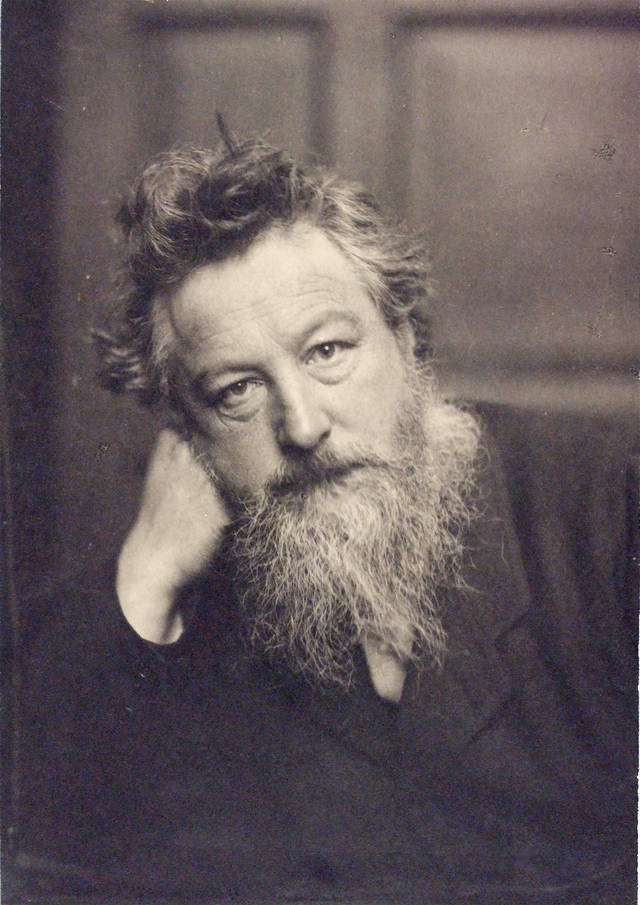

William Morris (1834-1896) “INSPIRE”

British textile designer, craftsman, writer and political activist William Morris was a key figure in the Arts & Crafts Movement.

Morris was born in affluence in Walthamstow, London, in 1834. His broker father bestowed an inheritance so large that Morris was never troubled about earning an income.

From his youth, Morris had a strong moral compass and social awareness. He was disgusted by the industrialism of the Victorian age, believing society based on mass production created alienation and division.

Matriculating at Oxford University Morris met the Pre-Raphaelite artist Edward Burne-Jones, who shared his views about the decline of the modern world. Burne-Jones introduced him to a group who were known as ‘The Set’ or ‘The Brotherhood’. Together they read medieval history, chronicles, and poetry, which celebrated themes of romantic chivalry and self-sacrifice. As a result, Morris developed a lifelong love of medieval history and art.

Combined with his hatred of modern industrialization, Morris sought to return to a medieval system that supported craft through artisan guilds, thereby raising the status of the artist or manufacturer. His vision was out of sync with Victorian Britain, where the status of the individual maker had been relegated to just another cog in a machine.

Morris’s ideas were influenced by art and social critic John Ruskin, who cautioned about the dehumanizing consequences of mass production. Industrialization, Ruskin believed, would eventually be the ruin of art and culture, and by this logic, it would lead to a destruction of civilization.

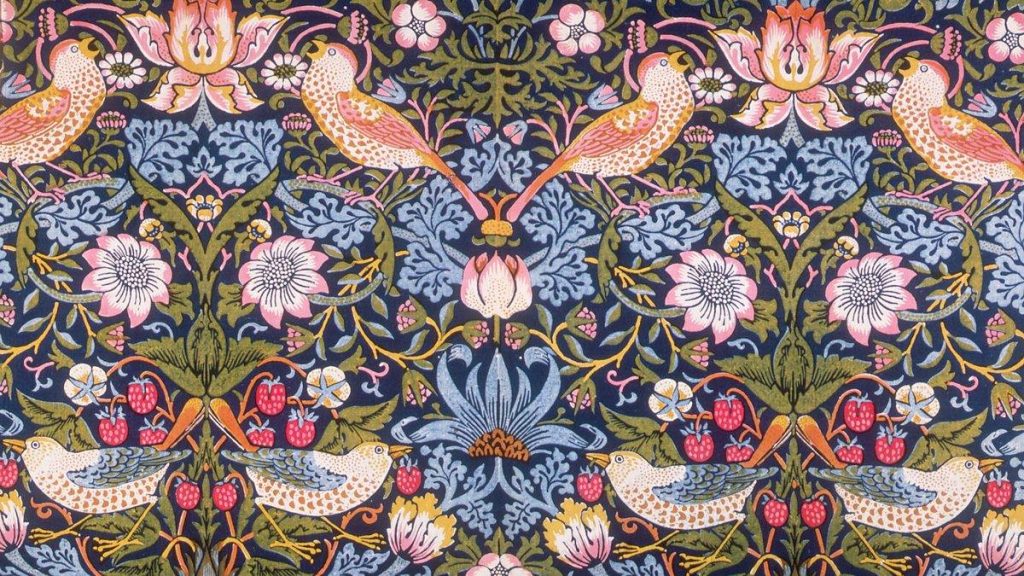

The Arts and Crafts movement drew upon several key principles which sprang from a fundamental respect for nature. Morris believed that the beauty of objects lay in both the visual aesthetic and the skill of the craftsperson.

The principles specified that only natural and local materials should be used, vernacular styles should be created from domestic, traditional techniques, simple forms should expose the construction processes, extravagant decoration was unnecessary, and natural motifs was the preferred theme.

Morris’ ideas manifested in Red House, a family home designed by Phillip Webb in Kent. The design aimed to be true to its materials and expressive of the site and local culture. When another re-Raphaelite artist Gabriel Dante Rossetti saw it for the first time, he declared it ‘more a poem than a house’. Expansive murals and hand-embroidered fabrics adorned the walls, creating a sense of an ancient manor house.

In 1861, Morris founded the Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co decorative arts firm with Burne-Jones, Rossetti and Webb. They brought together craftsmen of all kinds under one studio and sought to apply Ruskin’s philosophy to business. For Morris, this creating beautiful designs which were also functional. He wrote, ‘Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful.

’The medieval style of Morris’s work was well received. His approach to craftsmanship and labor became a model for numerous craft guilds and art societies.

In 1875, Morris & Company was founded as Morris took control of the company. It sold printed and woven fabrics, wallpapers, designs for carpets, rugs, embroidery and tapestry and offered an innovative ‘all under one roof’ retail experience.

Despite his privileged background, Morris became increasingly frustrated with politics, and founded the Socialist League in 1884. When Morris died in 1896, he was a household name, and his design principles still enjoy popular success today.